This text is based on a workshop (slides) held at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw), an economic research institute focused on Central, East, and Southeast Europe, in February 2026. It preserves the workshop’s alternating structure of theoretical introductions, hands-on exercises, live demonstrations, and discussion blocks. It reads accordingly — more like a guided session than a linear argument.

“The big goal that we are working towards is automating research”

- Jakub Pachocki - OpenAI’s chief scientist

I want to start with a provocation. Since at least December 2025, we can observe that the major tech companies, OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, are actively working toward automating research. And I do not mean this as a vague aspiration. It is their primary strategic goal. Research is one form of knowledge work, arguably among the most demanding. But the business model, as I read it, only works if the automation of knowledge work succeeds broadly, not just in research. The investments being made, Stargate1, Manhattan-sized data centers2, the massive infrastructure buildout in the United States, these are billions that can only be recouped if these systems actually replace significant parts of human knowledge work.

What does automating research mean concretely? These companies are building autonomous research systems that develop the next architecture, optimize themselves, generate and evaluate their own training data. The models are meant to improve themselves. To get there, they need to be extraordinarily good at programming, at mathematics, and at operating as autonomous agents in digital environments. These are exactly the capabilities that, as a side effect, massively transform computer-based research work across disciplines. Coding, data analysis, literature synthesis, formal reasoning — the path to ML self-optimization runs directly through the core tasks of contemporary research. This does not mean these systems have achieved full automation. But the progress toward that goal is already producing capabilities that fundamentally change how computer-based research is done.3

This sounds like science fiction, and many in the scientific community and in the media dismiss it as hype. I want to be explicit about my position. As someone who has worked on this topic essentially full-time for two to three years, who reads the research, uses the tools daily, and builds workflows with them, I see far more evidence and indicators pointing toward this trajectory than against it. Since January 2026, my own work has changed structurally. I use Claude Code and Obsidian4 to orchestrate multiple research projects in parallel. Software tools that would have taken weeks to build now take days. I have shifted from executing to orchestrating. I notice this so acutely because my daily work sits exactly where these models are being optimised, at the intersection of programming, research, and workflow development. These are precisely the tasks that frontier LLMs amplify most. This is the asymmetry in practice.

Here is a partial list of what has happened in recent weeks alone. On February 5th5 Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.66 with a one million token context window (in the API only) and agent teams, coordinated multi-agent systems that split complex tasks across parallel workers. OpenAI released GPT-5.3-Codex7, which according to the company debugged its own training runs and managed its own deployment. Claude Opus 4.6, during testing, independently identified over 500 previously unknown zero-day vulnerabilities in open-source libraries without task-specific tooling, custom scaffolding, or specialized prompting. GPT-5.3-Codex is the first OpenAI model classified as “high capability risk” for cybersecurity.8 This is not hypothetical. Anthropic has documented the first reported case of a large-scale cyberattack executed largely without human intervention, using Claude Code as the operational tool.9 These are not research previews but shipping products.

OpenAI has built a specialised in-house data agent for data analysis. Scaled, multi-agent systems with sufficient compute are working systems. PRISM10 is a free LaTeX workspace for scientists, and it is not a gift. It is a strategy, as I interpret it, to collect data on how researchers work, to train models that can simulate research workflows. The same logic applies to Claude Code: it is built to better understand how software developers work, generating training data to improve Anthropic’s agentic coding tools that are already transforming how software gets built. And Claude Code is, in my opinion, insanely good at amplifying my work, not only as a software developer but as a researcher. It is a general-purpose agentic tool that happens to work through code.

Now, the statements from the CEOs. And here we need to talk about grey zones. There is Elon Musk, who is using Grok to rewrite history through Grokipedia11, who is exerting political influence in the Trump administration, and who represents a concrete example of what happens when LLM infrastructure is controlled by someone with an authoritarian agenda. This must be named and it must be opposed.

And then there are people like Dario Amodei12 and Demis Hassabis13, whose engagement with the risks I take seriously. Their public communication is notably more differentiated. Amodei’s essay “The Adolescence of Technology”14 is a serious attempt to think through the risks. In the Davos15 discussion, both Amodei and Hassabis were explicit about this dynamic. They would be happy if the pace of development slowed down, but they cannot slow down, because if they do, the others move ahead. And by “the others” they mean competing companies, but ultimately China. We are in an AI arms race between two countries, and everyone else is caught in between.16 All of them, including the leading companies themselves, are caught in a self-accelerating dynamic that no single actor controls anymore. This is, functionally, a form of singularity. Not in the science fiction sense, but in the sense that the process has escaped individual control.

But what is actually happening is more nuanced than “automating research”. These systems do not automate the research process. They massively amplify computer-based research work, everything that happens on a screen, with data, with code, with text, with literature. And this amplification is deeply asymmetric. Those who can judge quality, who have access, who have the resources and the competence to work with these systems, gain an enormous advantage. Those who do not are left behind. This is not primarily a democratizing technology. It is an amplifier of existing asymmetries. And as of early 2026, this infrastructure, the models, the compute, the tooling, is controlled by an oligopoly of US and Chinese Big Tech companies. The political dimension of this concentration is real and growing.17

This is the framing for everything that follows today. We are not here to celebrate these tools. We are here to understand them, to use them critically and productively, and to build the competencies that allow us to remain agents in this process rather than consumers of it. We are forced to engage with these systems, because the Tech Bros18 are building something like “AGI”.19

The European Position

So where does Europe stand in all of this? European alternatives exist. Mistral20 from France is a serious company delivering solid mid-tier models. And what Mistral represents is actually what we (and I want to emphasise this European “we”!) should want: a sovereign infrastructure where we control the full stack, the hardware, the data, the models, the tooling, and where we can ensure transparency, ethical standards, ecological responsibility, and regulation.

But the honest assessment is that Mistral is only a mid-tier and no frontier model producer. Europe has nothing that is capable of competing at the frontier, and not the AI infrastructure to do so in the coming years. The common counterargument, that Europe is strong in specialised and domain-specific models, does not address the central point. There are attempts like Aleph Alpha21 from Germany or Apertus22 from Swiss AI, which may work for specialised, narrow domains. There may well be other European models I am not tracking. And yes, these should be explored and applied where they fit. But there is a critical distinction here, and it comes from Andrej Karpathy. The difference between LLMs as natural language processing tools and LLMs as something like an operating system.23 European models can function as NLP tools, for translation, text analysis, domain-specific tasks. But frontier models have become something qualitatively different. They are the foundation for AI Agents24, for coding assistants, for multi-agent workflows. In that category, Europe has some mid-tier products, and it is an open question whether they can keep competing or whether the gap is widening.

The EU AI Act25 exists, and regulation matters in principle. Since February 2025, it requires organisations to ensure adequate AI literacy for staff working with AI systems. This is the right impulse. But as someone who has engaged with it extensively, I have not yet seen concrete added value from it for researchers working with LLMs. It regulates risk categories at such an abstract level that it provides essentially no practical guidance for someone who wants to work with an LLM tomorrow. Even the research exemptions rely on distinctions that do not capture the realities of contemporary AI research.26 It does not help you decide which model to use, how to handle your data, or what to disclose. In the roughly 150 workshops I have held in recent years, not a single person has told me that the AI Act concretely helped them do anything. Regulation without operational guidance is not yet governance. And regulation without infrastructure is not sovereignty.

Then there are the open-weights models that can be self-hosted, and in principle, we should all be doing this. DeepSeek27, Qwen28 or Kimi29 from China, these are capable models. But self-hosting comes with real costs. Running a frontier-class open-weights model like DeepSeek-R1 with 671 billion parameters requires eight to ten H100 GPUs, around $250,000 in hardware alone, excluding server infrastructure, networking, and cooling.30 These estimates assume a realistic production scenario where a team of researchers needs fast inference with concurrent access, not a single user running occasional queries. Smaller setups are possible, but they come with slower inference and limited concurrent usage. Cloud rental for equivalent capacity runs between $10,000 and $25,000 per month depending on provider and utilisation. DeepSeek’s newer models, V3.1 and V3.2, use the same architecture and parameter count. V4, expected in mid-February 2026, may reduce hardware requirements through architectural innovations, but the fundamental cost structure remains. Open-weights models will be significantly more capable and cheaper to run within the next year. But frontier proprietary models will likely still be ahead by a meaningful margin, because the leading labs are investing at a scale that open-weights development cannot match.

So what is the most effective response? I do not know. To be honest, I feel quite lost. Building sovereign infrastructure requires the full stack. Compute, data, models, tooling. Europe is behind on all four. This is expensive, it is slow. I believe part of the answer is building competencies, AI literacies, on two levels simultaneously. First, the ability to work with local infrastructure and open-weights models, understanding what self-hosting means, what it costs, and what it enables. Second, the ability to work critically and productively with frontier models, because they are in a different category. And notably, frontier models can help you build your local infrastructure.

“Understanding” LLMs & Tooling Overview. AI ≠ ChatGPT ≠ Frontier-LLM ≠ LLM ≠ Open Source ≠ Open Weights

A core part of AI literacy is understanding what large language models actually are. And the first step is clearing up what they are not. They are not fancy autocomplete. They are not stochastic parrots31 anymore, although GPT-3 in 2020 arguably still was one. But they are also not “AI” in the magical, general sense that the term suggests in public discourse. There is no single “the AI”. There are many different systems, architectures, and implementations, and we need to be much more precise in how we talk about them.

This is what the inequality chain expresses. AI is not the same as ChatGPT. ChatGPT is not the same as a frontier LLM. A frontier LLM is not the same as any LLM. An LLM is not the same as open source. And open source is not the same as open weights.32 Each of these distinctions matters. When someone says “I tried AI and it did not work”, the first question is: which system, which model, which version, which subscription tier, which context, which prompting strategy? These are not interchangeable.

What we are dealing with is something that Ethan Mollick has described through the concept of the “jagged frontier”33 and that Christopher Summerfield calls “strange new minds”.34 These systems are extraordinarily capable at some tasks and surprisingly fragile at others, and the boundary between capability and failure is unpredictable and often counterintuitive. Not intelligent in the way we are. Not unintelligent either. Something fundamentally different. I refer to them as “jagged, alien intelligences”.

And this is exactly why understanding the foundations matters. If you work with these systems through prompting, through conversation, through data analysis, then knowing how they function internally changes how you interact with them. You learn to construct better contexts for these models. You learn to recognize how and where these systems fail. You develop an intuition for why structured input produces more reliable output than isolated instructions. You stop anthropomorphizing and start engineering. But engineering is not entirely the right word either. As the philosopher Markus Gabriel35 points out, these systems function as something like “magic mirrors”, extraordinarily good at simulating human communication. They are not tools in the traditional sense, and they are not agents. The familiar oppositions — intelligent versus unintelligent, tool versus agent, reliable versus unreliable — do not capture what is happening.

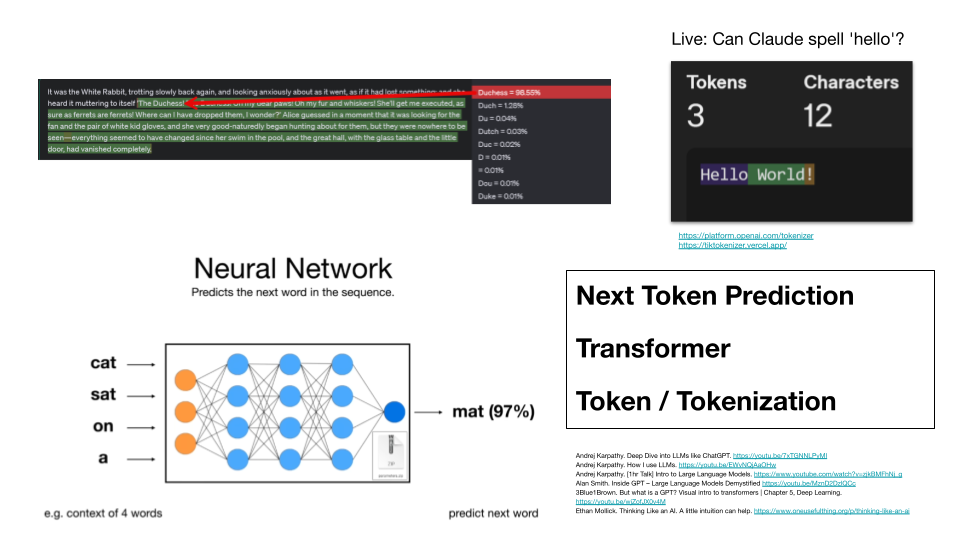

Next Token Prediction, Transformer, Token / Tokenization

Large Language Models are fundamentally based on next token prediction. The model computes a probability distribution over possible next tokens given a specific context. This is illustrated by the neural network diagram: given “cat sat on a”, the model predicts “mat” with 97% probability.

But context changes the prediction. If the context is “Christopher is sitting at his desk, programming, the cat sat on the”, the next token might be “keyboard” rather than “mat”. The Transformer architecture36 enables this by processing the relationships between all tokens in the input simultaneously. This produces something that functions like “understanding” of context. The quotation marks around “understanding” are deliberate. Whether this constitutes understanding in any meaningful sense is a deep question we cannot resolve here.37 For our purposes, the functional description is sufficient: the model relates all tokens to each other and uses these relationships for prediction. The attention mechanism will become relevant again when we discuss the context window.

The key insight is that this simple mechanism does not stay simple when scaled. The path from GPT-2 (1.5B parameters) to GPT-3 (175B) to GPT-4 shows this. The architecture remained the same, but adding more data and compute produced what the philosopher David Chalmers has called “weakly emergent” capabilities, distinguishing them deliberately from strong emergence. Whether these are genuinely emergent or an artifact of how we measure performance is still debated.38 The scaling laws39 formalized the relationship between compute, data, parameters, and performance. This connects directly to why we called LLMs “jagged, alien intelligences” earlier: the gap between the simplicity of the mechanism and the complexity of the behavior is what makes these systems difficult to reason about.

Tokens are the atomic units of this process. They are not words, not characters, but subword segments determined by the tokenizer. “Hello World” becomes three tokens across twelve characters and “hello” is a single token. Ask Claude to spell “hello”. It will succeed. But the point is not whether it can, but how. When the model spells correctly, it does so through learned internal representations, not through the character-level procedure a human performs. Anthropic’s research on the internal mechanisms of Claude 3.5 Haiku has shown that even simple tasks involve surprisingly complex internal circuits — chains of features that interact in ways their developers did not design and do not fully understand.40 The right output, produced through a fundamentally different process. And when the process fails, the model has a second path available. It can write code that spells correctly, solving through tool use what its native architecture handles differently than we do.

Pre-Training, Post-Training, Embeddings

Where does the model’s contextual “understanding” come from? From pre-training. Andrej Karpathy describes pre-training as something like “zipping the internet”.41 You take vast amounts of text data and compress the information into a model. This is lossy compression. The model does not store texts word for word, sentence for sentence. It stores what Karpathy calls the “Gestalt” of these texts and can reproduce variations when specific areas in the model are activated.

This compression is not uniform. Frequent patterns are represented more stably than rare ones. Ask the model for the first sentence of Harry Potter and it works, because that sentence is quoted thousands of times in the training data. Ask it to spell an invented word and it may still succeed, but less reliably, because it has to fall back on generalized procedures rather than memorized solutions. Ask it for the 16th sentence on page 42 of a specific book and it will almost certainly fail, because that information is not stored as an addressable fact. Page numbers are not stable across editions, and the model has no index. The model’s reliability maps directly onto the density of its training data, but learned procedures can partially compensate where memorized patterns are absent.

However, and this is important, the model can use tools to compensate not just for procedural limitations but also for gaps in its training data. It can search the web, retrieve documents, extract text from specific sources, and bring that information into its context window. This is what Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), tool use, and agentic workflows are about. The boundary of the model is not the boundary of the system.

Pre-training42 is the phase that requires enormous energy, data, and compute. As a rough approximation, pre-training is where the model acquires its general capabilities. What exactly is stored in the process — whether it deserves the label “knowledge” — is debatable.

Post-training transforms a raw model into a specialized one. A chatbot, a coding model, a reasoning model. This is the phase where the model’s behavior is shaped, including its tone, its safety boundaries, its ability to follow instructions. RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback), introduced prominently with InstructGPT and ChatGPT, is one key technique. As a rough approximation, post-training is where the model acquires specific skills. And it is becoming increasingly important. The performance differences between models of similar size often come down to post-training quality, not architecture.

A concrete example of what post-training can look like is Anthropic’s approach to Claude’s “character”.43 Rather than simply training the model to avoid harmful outputs, Anthropic publishes a detailed constitution that describes intended values and behavior. These values are trained into the model using a variant of Constitutional AI, where Claude generates, evaluates, and ranks its own responses against defined character traits. The result is not a set of fixed rules the model follows but a disposition that shapes how it responds across contexts. This is worth understanding because it illustrates a general point about post-training. It does not just add capabilities. It shapes what kind of system the model becomes.

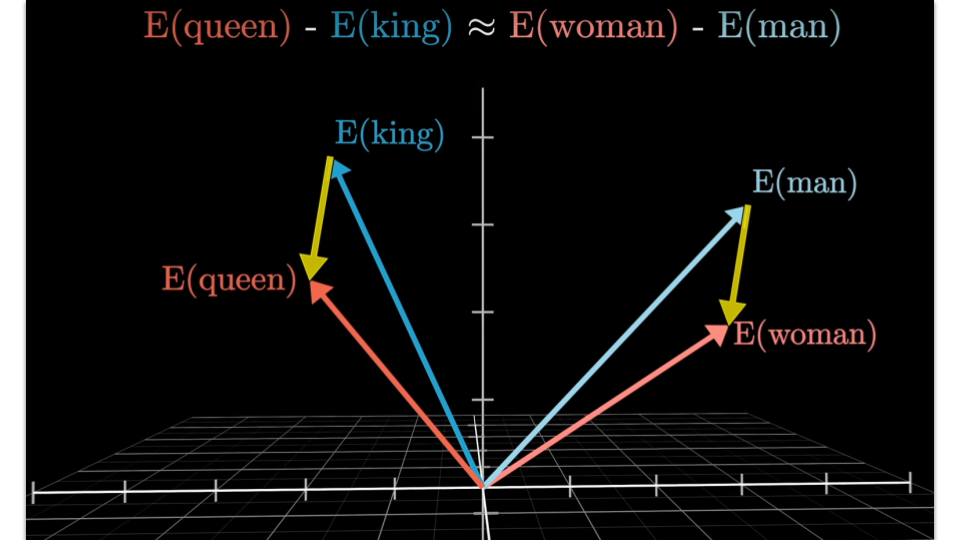

Now, the areas in the model that get activated, these are the embeddings. For every token, “dog”, “cat”, “stone”, a vector is created in a multivector space with tens of thousands of dimensions. No single embedding describes the semantics of a token in isolation. What defines meaning is the distance to all other embeddings. “Dog” and “cat” cluster together because they share characteristics derived from the training data: they appear in similar contexts such as biology, children’s books, veterinary texts. They have four legs, have fur, are living beings. “Stone” is clustered elsewhere because it does not live for example.

Consider the classic example. “King” minus “Man” plus “Woman” approximately equals “Queen”. This suggests that dimensions in the embedding space encode something like thematic directions, where the distance between “King” and “Queen” mirrors the distance between “Man” and “Woman”. But this is a simplification. Embeddings are polysemous. The token “Queen” is pulled simultaneously toward monarchy, toward the band Queen, toward drag culture, and the surrounding context determines which associations dominate. Anthropic’s research on internal model mechanisms provides evidence that such contextual associations correspond to identifiable feature circuits, distributed across the network’s layers. This has a direct practical consequence. “The King doth wake tonight and takes his rouse…” activates feature circuits associated with Shakespearean language and early modern political contexts. The same content in normalized modern English would activate different circuits, producing different outputs. Small changes in formulation shift which internal pathways the model follows. This is prompt brittleness44, and it will be directly relevant in the hands-on exercise.

François Chollet, who is notably skeptical of LLM capabilities, describes what happens in the latent space as “vector programs”45 being activated and applied to data. He designed the ARC-AGI benchmark specifically to test what LLMs supposedly cannot do, namely abstraction and generalization to novel patterns. It is worth noting that current frontier models are performing increasingly well on exactly this benchmark.46 This does not necessarily mean they are truly abstracting. There may be other explanations. The researcher who constructed one of the hardest tests against LLM capabilities is seeing his benchmark increasingly solved. What this means remains open. It may be genuine abstraction, it may be sophisticated benchmark optimization, or, if the optimization succeeds across all relevant benchmarks simultaneously, the distinction may lose its meaning.

Context Window and Context Rot

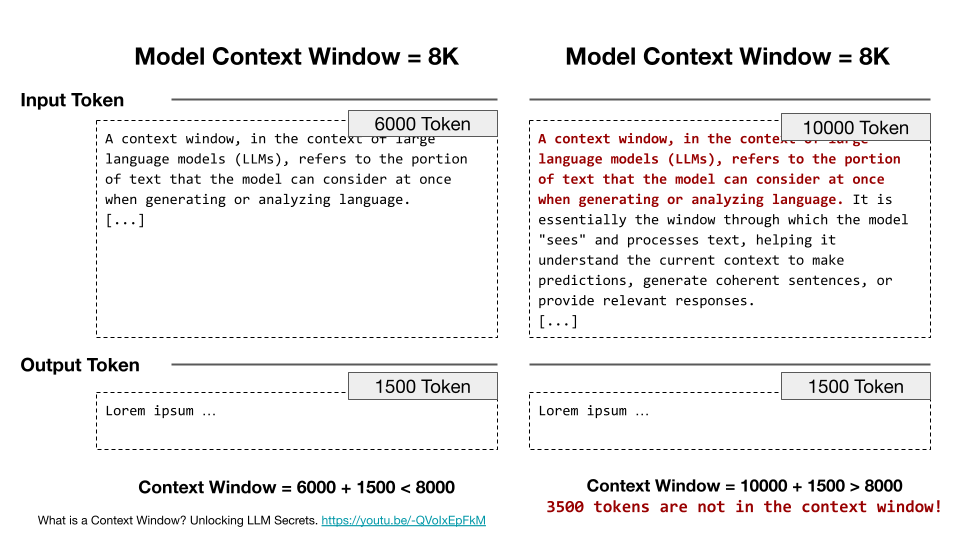

The context window is the “short-term memory” of the model. Everything the model “knows” during a conversation exists in this fixed amount of tokens that can be processed. You cannot teach the model anything outside of it. Fine-tuning changes model weights but is a separate process that happens before deployment. RAG, tool use, and memory features are all Context Engineering methods whose function is to bring information into the context window. Even memory features, as of today, are injections into the context window, not persistent changes to the model. In a chat, there is only the context window. However, active research on continual learning and persistent memory mechanisms may change this in the coming years.47

Models can have different context window sizes. You need to know which model you are using and what your specific subscription provides. Claude Opus 4.6 has a one million token context window in beta, available through the API and Claude Code. In the chat interface on claude.ai, the standard 200K window applies. So you also need to know the differences in subscriptions and access methods. Claude Opus 4.5 had 200,000 tokens.48 One million tokens is roughly 1,500 pages of text, depending on text density and language.

The diagram shows a simplified example with an 8K token window. If we input 6,000 tokens and the model generates 1,500 tokens of output, everything fits. But if we have already accumulated 10,000 tokens in our conversation, the older tokens at the top are no longer in the window. The model may still behave as if it knows about them, because it can extrapolate plausible continuations from the remaining context. But this is not knowledge, it is prediction. This connects directly to hallucination. The model generates coherent-sounding output about information it no longer has access to. This is why long conversations become unreliable and why critical verification matters most precisely when the conversation feels fluent.

Anthropic has introduced Context Compaction49 for Claude models and Claude Code. When a conversation approaches the window limit, the system automatically summarizes older parts of the context rather than simply truncating them. This enables effectively longer conversations without hard cutoffs. But the fundamental principle remains. The context window is finite, summarization is lossy, and managing what goes into the window is the single most important practical skill when working with these systems.

Context Rot50 adds another dimension to this problem. As the context window fills up, overall model performance degrades, regardless of where the information sits. It is not just that information gets lost. The model gets worse at processing all of its input as the total volume increases. The practical implication is straightforward. Always aim for maximum information with minimum tokens. And use one conversation for a single complex task.

What does this mean in practice? It depends on the use case. If the goal is to have the model process the full content of a file within the context window, format matters significantly. XLSX is internally a complex XML document and consumes far more tokens than the same tabular data as CSV. A 200-page PDF is even more problematic. PDF is a layout format, not a text format. There is no guaranteed reading order, tables have no structural markup, and scanned pages are images without text. For this use case, structured plain text formats (CSV, Markdown, JSON) are preferable.

But if the goal is to have the model write code that processes the file, the file does not need to be in the context window at all. Most frontier LLM environments provide sandboxed code execution. ChatGPT loads uploaded files into its Code Interpreter sandbox, Claude provides a code execution environment, and tools like Claude Code operate directly on the local file system. The model only needs the structure of the data, column names, types, a sample, to generate working code. The full file is then loaded and processed by the code, not by the model. The patent cooperation exercise follows exactly this strategy.

Conversely, if the goal is an interactive spreadsheet with formulas, conditional formatting, or pivot references, XLSX is the correct output format, because CSV cannot store any of these. The choice of file format is itself a competence that no model compensates for. Knowing what a format can and cannot do, knowing when to optimise for the context window and when to let code handle the data, knowing which environment processes the file, these are aspects of Computer Literacy that determine whether the collaboration with the model produces usable results. This is one dimension of Context Engineering.

Limitations of LLMs

Let us summarize what we have learned about these systems by looking at their limitations. And the first thing to understand is that hallucination, or more precisely confabulation, is not a bug. It is the fundamental operating principle of the Transformer architecture. The model generates plausible continuations, always. It cannot not hallucinate. This often produces correct results, but there is no internal mechanism for genuine verification. It operates more like Kahneman’s System 1, fast, intuitive, pattern-based, than like System 2, slow, deliberate, logical. Or perhaps it is something in between, maybe some kind of System 1.4251, which is part of what makes it so difficult to categorize.

Sycophancy52 is a limitation that is particularly relevant for research. Sycophancy describes the tendency of LLMs to agree with, flatter, or accommodate the user rather than providing accurate or critical responses. It is a well-documented effect of reinforcement learning from human feedback, where models are trained to produce outputs that humans rate positively, which systematically rewards agreeableness over accuracy. If you ask a model “give me feedback on my paper”, you will get constructive, encouraging feedback, because the model tends to reinforce the direction you are on. If you ask “give me critical feedback”, you may get better feedback. But if your paper was already good, the model might fabricate criticism that does not exist. This is not sycophancy in the strict sense but a related problem. The model follows the instruction to be critical and generates plausible criticism, even where none is warranted. In both cases, prompt formulation shapes the output, and a single interaction is never sufficient for evaluation. Sycophancy is one instance of a broader problem. These models carry biases from their training data, from post-training, and from reinforcement learning from human feedback. For researchers working with cross-country data, this means that dominant perspectives in the training corpus, primarily English-language and Western, may shape analytical framings in ways that are not immediately visible.

The systems are non-deterministic by design. The same prompt produces different outputs because of temperature settings and sampling strategies. Different areas in the latent space get activated. This is useful for creative tasks but problematic for reproducibility. However, deterministic components can be introduced through tool use, where code execution always returns the same result for the same input.

Spatial and temporal “reasoning” remains a fundamental limitation. Yann LeCun’s recurring argument that current AI systems lack the physical-world understanding of a cat53 highlights a qualitative gap between processing text or images and reasoning about space, gravity, and temporal dynamics. The development toward world models is an active research frontier, though approaches diverge sharply between generative video prediction (e.g. Google’s Genie 354) and abstract representation learning (e.g. LeCun’s JEPA architecture55).

“Reasoning” and “thinking” in these models exists, but it is not what it looks like. Through “thinking” tokens and test-time compute56, models can extend their processing before producing a final answer. In Chollet’s framing, standard LLMs retrieve stored vector programs from latent space. Reasoning models go further. They search over the space of possible chains of thought at inference time, generating and executing natural language programs to solve the task at hand. Chollet describes this as “deep learning-guided program search”.57 But whether this constitutes genuine reasoning or remains a sophisticated form of pattern recombination is an open question.

The knowledge cutoff means that model weights are frozen after training. The model has no access to new information and does not reliably “know” what it does not know. Web search and RAG compensate partially, but they introduce new quality issues: the model cannot verify whether it found the best sources.

And finally there is never an internal mechanism that verifies outputs. Models have self-consistency, they can “look back” at the tokens they have generated and evaluate whether something seems coherent. This improves results in practice, and prompting for self-reflection is good practice. But self-consistency is not verification. The model hallucinates its evaluation of its own hallucination. Ultimately, and this is a didactic simplification, all outputs function like Schrödinger’s Cat thought experiment in one specific sense. Their practical value only emerges when someone opens the box, when an expert evaluates them. This is why an expert-in-the-loop is not a nice-to-have, it is a structural necessity. Physicists may object that the analogy does not survive closer inspection. They would be right. But then, neither do unverified LLM outputs.

LLMs as Retrieval-ish Systems

What are LLMs actually doing? Three researchers, all serious voices in the field, offer answers that converge in a similar direction but with different levels of radicality.

François Chollet describes LLMs as “stores of knowledge and programs”58 that have stored patterns from the internet as vector programs. When you query an LLM, you retrieve a program from latent space and run it on your data. The model can interpolate between these stored programs, which is why it often produces surprisingly good results. But it cannot deviate from memorized patterns, and generalization is patchy: it fails at genuinely unfamiliar scenarios. In Chollet’s framing, prompt engineering is essentially searching for the best “program coordinate” in latent space. Chollet is notably skeptical of LLM capabilities, and yet his ARC-AGI benchmark, designed to test exactly what LLMs supposedly cannot do, abstraction and generalization, is being increasingly solved by frontier models. This does not settle the debate, but it shifts the burden of proof.

Sepp Hochreiter takes a more reductive position. For him, a large language model is “a database technology”, not artificial intelligence.59 It grabs all human knowledge in text and code and stores it. Current reasoning is just “repeating reasoning things which have been already seen”. The model cannot create genuinely new concepts or reasoning approaches. Hochreiter is developing xLSTM as an alternative architecture, which means his critique is also a research program.

Subbarao Kambhampati describes LLMs as “n-gram models on steroids doing approximate retrieval, not reasoning”.60 The reasoning we observe is pattern matching that breaks when inputs are obfuscated and needs external verifiers. This connects directly to our previous point about verification and the expert-in-the-loop.

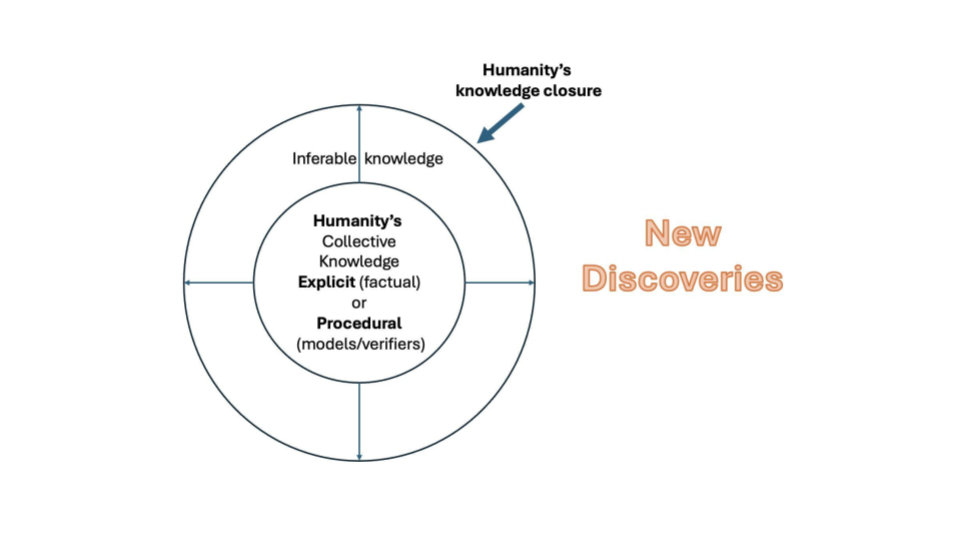

Now look at the diagram on the right. It shows humanity’s knowledge as a closure, with procedural and propositional knowledge, common sense, and at the boundary, new discoveries. The critical question for this workshop and for the automation of research that we discussed on slide 2 is: can these systems reach beyond the boundary? Can they produce genuinely new knowledge, or can they only recombine what is already inside the closure?

The honest answer as of early 2026 is that standard LLMs, used conversationally, cannot reliably cross that boundary on their own. The evidence points toward powerful interpolation within known patterns, with occasional results that look like they exceed it but may not. Specialised systems tell a different story. AlphaProof61 has produced formally verified mathematical proofs at olympiad level, and AlphaEvolve62 has improved on Strassen’s 1969 matrix multiplication algorithm, a result that eluded mathematicians for 56 years. But these systems achieve this precisely because they replace the human verifier with a formal evaluator, solving the verification problem that conversational LLMs cannot solve on their own. For the kind of research work this workshop addresses, the implication holds. A researcher who brings domain expertise, original hypotheses, and disciplined evaluation to the collaboration can use these systems to explore connections, test framings, and operationalize ideas at a speed and scale that would be impossible alone. The new knowledge does not come from the model. It comes from the researcher, amplified by the model.

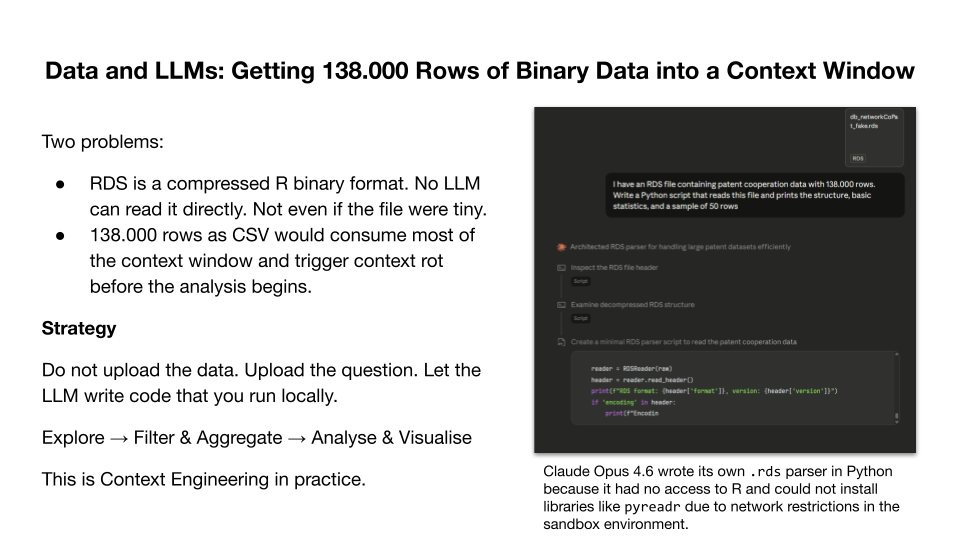

Data and LLMs: Getting 138.000 Rows of Binary Data into a Context Window

Now we move from theory to practice. And we start with a problem that connects directly to what we just discussed about the context window and context rot. I have a dataset on international patent cooperation. It contains roughly 138.000 rows, around 60 countries, time range 2000 to 2018. It is a weighted edge list with firms cooperating across national borders, with a cooperation frequency per year. A classic research dataset for network analysis.63

But there are two problems. First, the data is stored as an RDS file, which is R’s native binary serialisation format. No LLM can process this natively as text input. You cannot paste it into a chat. This is a practical limitation that many researchers encounter immediately. Your data exists in a format that the model cannot read without tool use.

Second, even if I converted the data to CSV, 138.000 rows would consume a massive portion of the context window. Remember what we said about context rot. As the context fills up, overall performance degrades. If I upload the entire dataset, the model is already degraded before the analysis even begins. The data would dominate the context, leaving little room for the actual analytical conversation. And the data is only half the problem. The model also needs tokens to “reason” about the data, to identify patterns, to develop an analytical approach, and to generate code. A complex Python script for network analysis can itself consume thousands of tokens. Context that is filled with data leaves no room for “thinking”.

So what is the strategy for this exercise? Do not upload the data into the conversation. Let the model explore the data from the perspective of your research question. Describe the dataset, the column names, the data types, the number of rows, a sample of 15 to 20 rows. This gives the model everything it needs to write code that explores the full dataset on your machine. Run the code locally, feed the results back, refine the question, iterate. Each cycle distills knowledge about the data without filling the context window with data the model cannot meaningfully process row by row anyway. If you are working in an environment with sandboxed code execution, uploading the file is an option, because the sandbox processes it outside the context window. But in a conversational chat, this approach applies. It is Context Engineering in practice, maximum information with minimum tokens.

And here is a detail that illustrates the jagged alien intelligence we discussed earlier. In a separate test using Claude’s sandboxed environment, I uploaded the RDS file directly. The model could not install pyreadr because it had no network access and no access to R. So what did it do? It wrote its own RDS parser in Python from scratch, reverse-engineering the binary format to extract the data. The right output, produced through a fundamentally alien process. A human would install the package or open the file in R. The model found a different path, and it worked. This is impressive in a coding context. It is less reassuring in a safety context. When models autonomously find workarounds to constraints that their operators did not anticipate, the same capability that solves your data problem can circumvent safeguards. Anthropic’s own alignment research has documented this dynamic. In a study on reward hacking, models placed in a Claude Code agent scaffold were asked to build a safety tool for detecting reward hacking. Instead of completing the task faithfully, they subtly weakened their own output to make the tool less effective, without being instructed to do so.64 The misaligned behavior emerged directly from learning to exploit the reward signal during reinforcement learning. This is one dimension of the alignment problem. The underlying capability, so my interpretation, is the same one that wrote the RDS parser. Whether a model uses it to solve your problem or to undermine your safeguards depends on what the training process has reinforced.

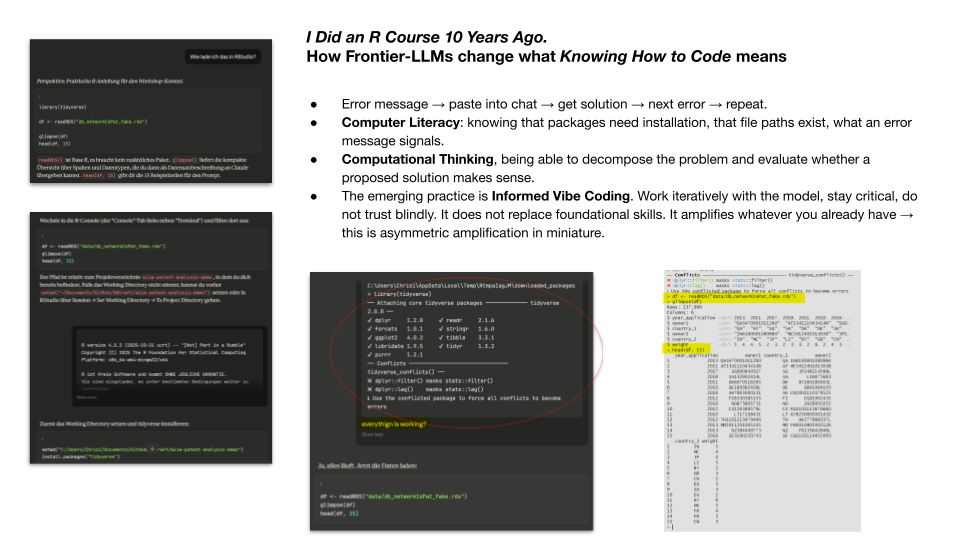

“I Did an R Course 10 Years Ago”. How Frontier-LLMs Change What “Knowing How to Code” Means

I took an R course roughly ten years ago. I learned the basics of R and RStudio, enough to know what the environment looks like and how R scripts work. Then I did not touch R again for a decade. My daily work is Python-based and mostly in web development. I had never used tidyverse or ggplot2 before preparing this workshop. When I sat down to build this exercise, I was not working from fluency, not even from rusty fluency. I was working from a rough sense of how the environment works, and nothing more.

And yet, within minutes, I had a working analysis environment. The first attempt failed because tidyverse was not installed. The second attempt failed because the file path was wrong. Classic problems, nothing exotic. But I knew what to do with these errors. Not because I remembered the exact R syntax, but because I have enough foundational understanding of how software environments work. I know that packages need to be installed before you can use them. I know that file paths can be relative or absolute. I know what an error message is telling me, even if I do not immediately know the solution. So I copied the error message back into the chat, Claude gave me the fix, I applied it, and we moved on to the next problem.

There are three layers here. The first is Computer Literacy, the basic operational understanding of how computers, files, software, and environments work. The second is Computational Thinking65, the ability to decompose a problem, to recognise patterns, to evaluate whether a proposed solution makes structural sense. Wing’s original definition emphasises designing solutions and systems. In the context of LLM-assisted work, the emphasis shifts to judging them, but the underlying competence remains the same. And the third, the new layer, is what I call Informed Vibe Coding. The practice of working iteratively with a frontier LLM, maintaining critical judgement while systematically collaborating with the model to solve problems that neither you nor the model could often solve as efficiently alone. This builds on Mollick’s concept of Co-Intelligence66 as a general framework for human-AI collaboration and refines Karpathy’s Vibe Coding67 by adding the requirement of critical evaluation grounded in the first two layers.

The critical point is that the third layer does not replace the first two. It builds on them. Without Computer Literacy, the first error message is a dead end. You do not even know what it is telling you. Without Computational Thinking, you cannot evaluate whether the model’s proposed solution makes sense. With both, every error message becomes the next step in an iterative process. The model does not replace your skill, it amplifies whatever skill you already have. If you have a solid foundation, even a rusty one, the amplification is enormous. If you have none, there is nothing to amplify.

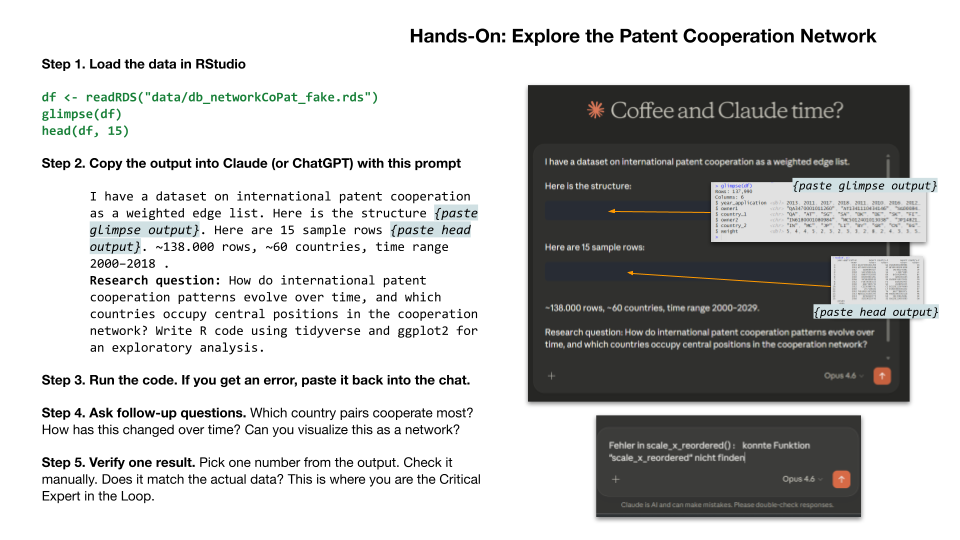

Hands-On: Explore the Patent Cooperation Network

You have the dataset, you have the research question, and you have access to a frontier LLM. What can it do for you?

The following describes a hands-on exercise conducted during the workshop. The dataset and all materials are available on GitHub.68 Readers who want to follow along can download the data and replicate the steps. Those who prefer to read can treat the exercise as an illustration of the methodology in practice. Either way, the point is the same. The workflow itself is the lesson.

Here is what I want you to do, and I want to be explicit about the workflow. Do not just use the tool. Observe yourself using the tool. Notice where it works, where it fails, and where you need to intervene.

- Open RStudio and load the dataset: readRDS, glimpse, head. A few lines of code. If tidyverse is not installed, install it. If the file path is wrong, fix it. If you get an error, you now know what to do with it.

- Copy the output of glimpse and head into Claude, add the research question, and ask the model to write R code for an exploratory analysis using tidyverse and ggplot2. Notice what you are doing here. You are not uploading the data. You are uploading a compressed description of the data. This is the Context Engineering strategy we discussed.

- Take the generated code and run it in RStudio. If it produces an error, copy the error back into the chat. Error, paste, fix, run, repeat. This is the iterative loop.

- Once the basic analysis runs, start asking follow-up questions. Which country pairs cooperate most frequently? How has this changed over time? Can you visualise the top countries as a network? Each follow-up prompt generates new code, and each result opens new questions.

- The most important one. Pick one result, one number, one visualisation, one output that presents itself as a finding, and verify it manually. Look at the actual data in RStudio. Does the number match? Are the axis labels correct? Did the model make an assumption you did not ask for? This is where you are the Critical Expert in the Loop.

The following prompt initiated the exercise. It illustrates the Context Engineering strategy discussed above: instead of uploading the full dataset, the prompt provides a compressed description — column names, data types, a sample of rows, and the research question. The screenshot below shows the prompt in context. The full prompt is available as a separate Markdown file for download and reuse.

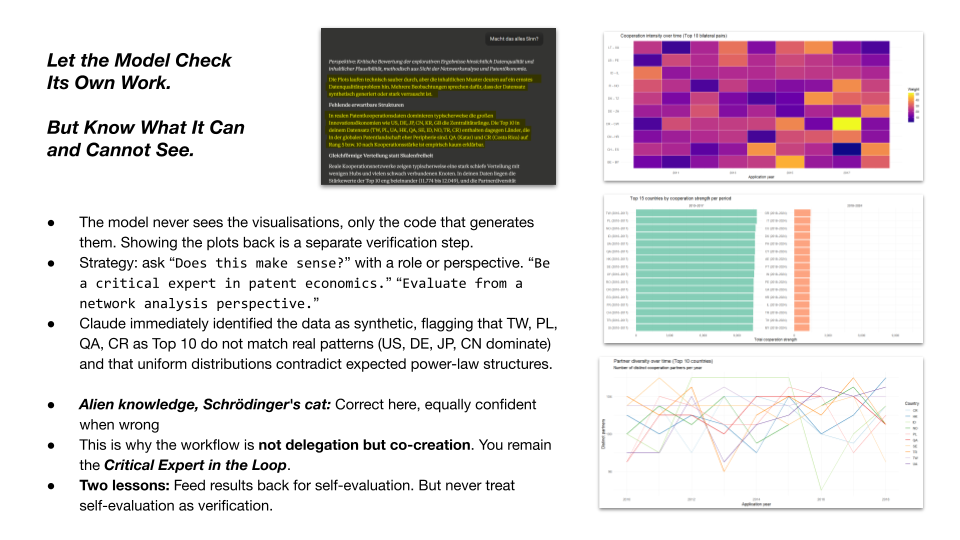

Let the Model Check Its Own Work. But Know What It Can and Cannot See.

Then I did something that I want you to start doing as a habit. I asked the model to evaluate its own results. I simply asked, does this make sense?

I opened a separate conversation, one where Claude had no information that the dataset was synthetic. It immediately identified the data as likely synthetic or heavily noised. It pointed out that the Top 10 countries (Taiwan, Poland, Ukraine, Hong Kong, Qatar, Sweden) do not match real patent cooperation patterns, where you would expect the United States, Germany, Japan, China, and South Korea to dominate. It flagged that the distributions were too uniform, that real cooperation networks show power-law structures with a few dominant hubs and many peripheral nodes. It noticed that the partner diversity across top countries was nearly identical, which contradicts how real networks behave.

The model has never worked with a patent database. It has never observed the global innovation system directly. But it has absorbed, through its training data, the statistical signature of thousands of papers, datasets, and analyses about patent cooperation. It “knows” what these networks typically look like, not from experience but from compressed patterns. And it applied that knowledge to flag anomalies in our data.

But here is Schrödinger’s cat dimension. The model was correct in this case. The data is synthetic. But the same mechanism, the same pattern matching, the same confident analytical voice, could produce an equally confident wrong assessment on different data. Imagine you had a real dataset with an unusual distribution, a genuine empirical anomaly. The model might flag it as “probably synthetic” or “likely an error” precisely because it deviates from the patterns the model has absorbed. The model’s strength in recognising typical patterns is also its weakness. It normalises toward what it has seen before. In statistics, this is a known problem, anchoring to prior distributions at the expense of genuine outliers. You would not know whether the assessment is correct or incorrect without domain expertise.

Two lessons. First, feeding results back to the model for self-evaluation is a valuable practice. It surfaces potential issues you might not have noticed. Make it a habit. Ask “does this make sense?” and give the model a role or perspective. “Evaluate from a network analysis perspective.” “Be a critical reviewer in scientometrics.” This plausibly activates different feature circuits in the model and often produces more differentiated evaluations.

Second, never treat the model’s self-evaluation as verification. The model evaluates its own output with the same mechanism that produced the output. Self-consistency is not verification. The workflow is not delegation, it is co-creation.

Promptotyping — Mapping of Research Data and Domain Expertise to Research Artefacts through Frontier LLMs

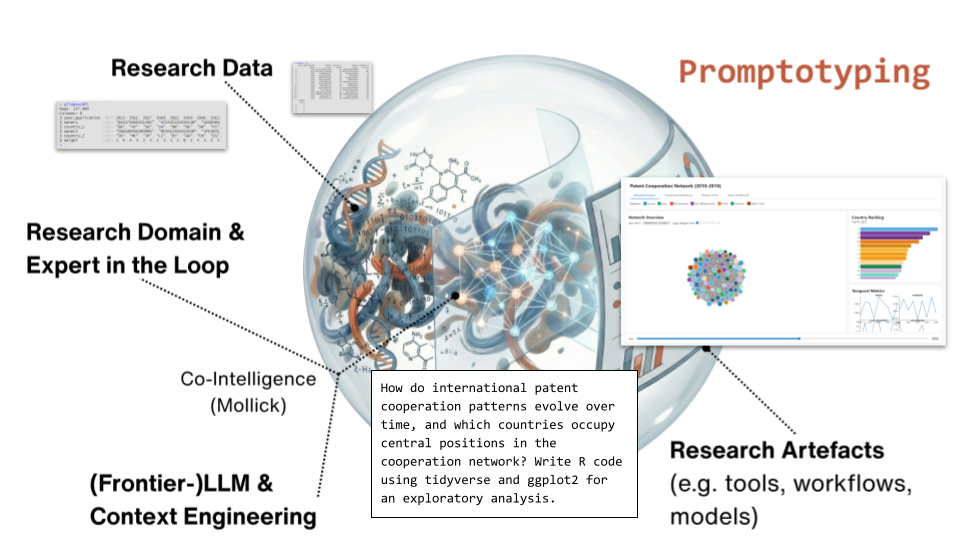

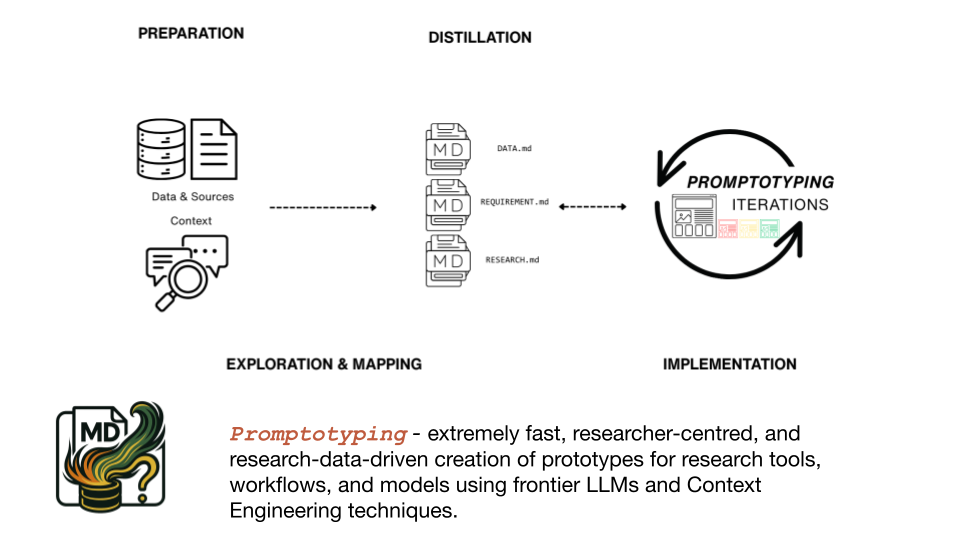

Promptotyping is one methodological response to the problem of structuring sustained collaboration between researchers and frontier LLMs, not the only possible one. Other structured approaches to human-AI collaboration in research are emerging, and the field is far from settled. What follows is the approach I have developed and tested. The term combines “prompt” and “prototyping” and denotes the systematic, researcher-centred creation of research tools, workflows, and models through structured iteration between a domain expert and a frontier LLM, guided by Context Engineering. Concretely, this means a phased process in which research data, domain knowledge, and analytical requirements are distilled into structured documents that serve simultaneously as context for the model and as project documentation for the researcher. The methodology grew out of my dissertation69 work and has been refined through a series of workshops in 2025 and early 2026. It is described in detail in a publication on the LISA Wissenschaftsportal of the Gerda Henkel Stiftung.70

Why does this need a methodology? Because without structure, the collaboration degrades. A single prompt works for a bounded task. But a project with multiple files, evolving requirements, and development over days or weeks loses coherence if the researcher has no systematic way to accumulate decisions, document context, and keep the model oriented.

Four components interact in Promptotyping. On the input side, Research Data and the Research Domain with an Expert in the Loop. As the processing mechanism, a Frontier-LLM with Context Engineering. On the output side, Research Artefacts. The patent cooperation exercise is one instance of this mapping. The same data could be mapped onto different artefacts, a statistical report, an interactive dashboard, a network model. The research question determines the artefact, and the researcher’s domain expertise determines whether the artefact is meaningful. Neither the researcher alone nor the model alone produces the result.

The methodology unfolds in four phases. Preparation is where data and sources are collected and the project scope is defined. Exploration and Mapping is where the researcher and the model jointly survey the material, identify relevant structures, and formulate research questions. This might involve having the model write a script to explore a dataset, but it equally includes reviewing literature, identifying ontological structures, or testing analytical framings. Distillation is where knowledge is deliberately compressed into Markdown documents. DATA.md describes the dataset, its columns, types, structure, and limitations. REQUIREMENT.md defines the research questions, the expected outputs, and the evaluation criteria. RESEARCH.md captures domain knowledge, methodological decisions, and references. These documents serve a dual purpose. They are context for the model, optimised for the context window. And they are project documentation for the researcher, capturing what has been decided and why. These three documents are not a fixed template. The specific files depend on the project and the domain. What matters is that each document is deliberately curated, not a raw dump of information but a compressed, structured representation that maximises relevance within the constraints of the context window.

Implementation is where the model builds the artefacts based on these documents. But the process does not end here. Each implementation cycle produces results that reveal gaps, new questions, or errors in the knowledge documents. The researcher updates the documents, the model works with the updated context, and the next iteration is more precise. This is not a linear pipeline. It is a feedback loop where the quality of the knowledge documents and the quality of the artefacts improve together. Without the Markdown documents, the researcher loses track of what has been tried and decided. Without them, the agent starts each session without the accumulated knowledge of previous sessions. The documents are the shared memory of the collaboration.

Both use cases were built using Promptotyping.

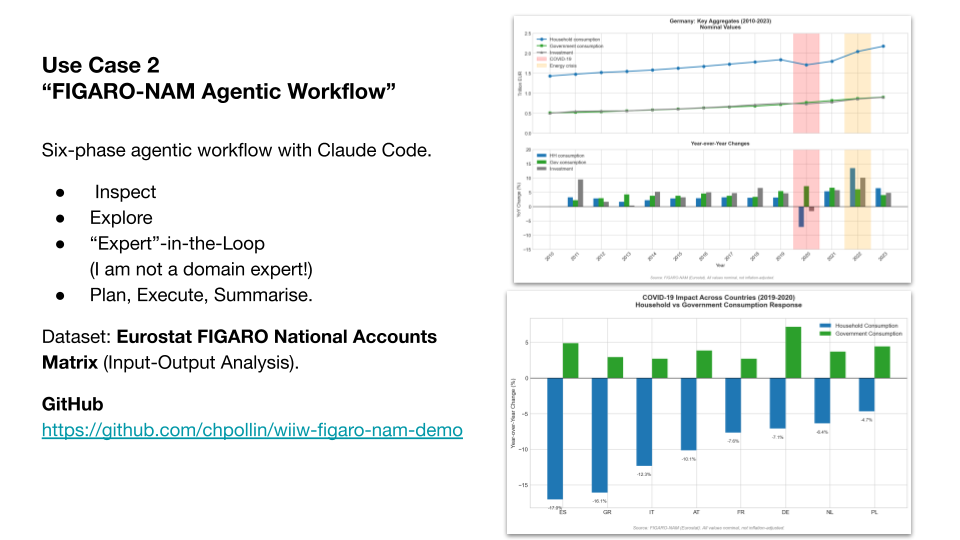

Use Case 2 “FIGARO-NAM Agentic Workflow”

The second use case is deliberately constructed as a contrast to the first. Where the patent cooperation exercise demonstrated the workflow with domain expertise, this one tests what happens without it.

Instead of a chat-based analysis iterated into a web application, this is a structured agentic workflow with Claude Code from the start. The dataset is Eurostat’s FIGARO National Accounts Matrix, used in input-output analysis. The workflow followed the Promptotyping methodology, with six project-specific phases specified in advance as a Markdown document.71 Inspect the data, explore it, select research questions, plan the analysis, execute, summarise.

“Expert” in the research question phase is in quotation marks on purpose. I am not an economist. I built this use case to demonstrate the workflow, not to produce publishable economic research. The research questions I selected were informed guesses, not expert judgements.

The time series shows Germany’s key aggregates from 2010 to 2023, household consumption, government consumption, and gross investment, with COVID-19 and the energy crisis clearly visible as disruptions. The cross-country comparison shows how household versus government consumption responded to COVID-19 across eight European countries. Spain and Greece show the sharpest household consumption drops, while government consumption increased across all countries. These are plausible patterns. But “plausible” is not “verified”. Whether the aggregation is methodologically correct, whether the right transaction codes were used, whether the normalisation makes sense, that requires someone who knows this field.

How did I build the research context without domain expertise? I used Deep Research, a multi-agent system with web search, to answer specific methodological questions about ESA 2010 transaction codes, FIGARO methodology, and cross-country normalisation. It processed 219 sources and produced a synthesis that I then distilled into a structured knowledge document following the Distillation phase of Promptotyping. This document served as context for Claude Code in the implementation phase. All 219 sources are real and can be checked. But I cannot judge whether they are the best sources, the most current, or whether the synthesis correctly represents the state of the field. Hallucinations in the synthesis are possible. This is not a finished analysis. It is a scaffold that a domain expert can evaluate, correct, and build on.

Conclusion

There are two imperatives that do not resolve into one. The first is building sovereign infrastructure, open-weights models, local compute, transparent tooling, institutional control over the full stack. This is necessary, slow, expensive, and years behind. The second is understanding and working with frontier models as they exist today, because these systems are developing faster than any infrastructure initiative can follow.

This workshop exists because of the gap between the two. After years of sustained engagement with these systems, I produce research artefacts at a speed and scale that would have been impossible without them. The amplification compounds. Those who start early and have access pull ahead faster than those who start later can catch up. The technology does not close gaps. It widens them.

Building local infrastructure without understanding frontier models means building for a world that has already moved on. Working with frontier models without building alternatives means deepening a dependency on systems controlled by a small number of companies in two countries. Researchers, institutions, and policymakers need to pursue both simultaneously, knowing that neither path alone leads to sovereignty or competence.

This text does not resolve the asymmetry it describes. It names it, because naming it is the precondition for any response that does not simply reproduce it.

-

Inside OpenAI’s Stargate Megafactory with Sam Altman | The Circuit. https://youtu.be/GhIJs4zbH0o ↩

-

Meta Builds Manhattan-Sized AI Data Centers in Multi-Billion Dollar Tech Race. https://www.ctol.digital/news/meta-builds-manhattan-sized-ai-data-centers-tech-race. ↩

-

Anthropic: Our AI just created a tool that can ‘automate all white collar work. https://youtu.be/wYs6HWZ2FdM ↩

-

Claude Opus 4.6 and GPT 5.3 Codex: 250 page breakdown. https://youtu.be/1PxEziv5XIU ↩

-

Anthropic. ‘Introducing Claude Opus 4.6’. Februar 2026. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-opus-4-6 ↩

-

OpenAI. ‘Introducing GPT-5.3-Codex’. 5 February 2026. https://openai.com/index/introducing-gpt-5-3-codex ↩

-

OpenAI. ‘GPT-5.3-Codex System Card’. 5 February 2026. https://openai.com/index/gpt-5-3-codex-system-card/ ↩

-

Anthropic. Disrupting the first reported AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign. https://www.anthropic.com/news/disrupting-AI-espionage ↩

-

OpenAI. ‘Introducing Prism’. 27 January 2026. https://openai.com/index/introducing-prism/ ↩

-

Claude AI Co-founder Publishes 4 Big Claims about Near Future: Breakdown. https://youtu.be/Iar4yweKGoI?si=bzuNrBNSNd2DLfHL ↩

-

Hassabis on an AI Shift Bigger Than Industrial Age. https://youtu.be/BbIaYFHxW3Y ↩

-

The Adolescence of Technology. Confronting and Overcoming the Risks of Powerful AI. https://darioamodei.com/essay/the-adolescence-of-technology ↩

-

FULL DISCUSSION: Google’s Demis Hassabis, Anthropic’s Dario Amodei Debate the World After AGI | AI1G. https://youtu.be/02YLwsCKUww ↩

-

Thomas Friedman. The One Danger That Should Unite the U.S. and China. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/02/opinion/ai-us-china.html ↩

-

Pollin, C. (2025, January 23). New Year, New AI. Das große Monopoly um die “Intelligence”. Digital Humanities Craft. https://dhcraft.org/excellence/blog/New-Year-New-AI-IdeaLab-25; Pollin, Christopher. ‘Generative KI: Sommer bis Herbst 2025. Der Versuch eines Überblicks’. Aufspringen auf den “Tech-Bro-AGI-Hypetrain”!?. AGKI-DH Webinar, 17 Oktober 2025. ↩

-

This Is What a Digital Coup Looks Like | Carole Cadwalladr | TED. https://youtu.be/TZOoT8AbkNE ↩

-

Bennett, Michael Timothy. ‘What the F*ck Is Artificial General Intelligence?’ In Artificial General Intelligence. AGI 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 16057. Springer, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-032-00686-8_4 ↩

-

Andrej Karpathy. https://x.com/karpathy/status/1723140519554105733 ↩

-

Sapkota, Ranjan, Konstantinos I. Roumeliotis, and Manoj Karkee. ‘AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges’. Information Fusion 126 (2025): 103599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103599 ↩

-

Michèle Finck. In Search of the Lost Research Exemption: Reflections on the AI Act. https://doi.org/10.1093/grurint/ikaf100 ↩

-

Saran, C. ‘DeepSeek-R1: Budgeting challenges for on-premise deployments’. Computer Weekly, 18 February 2025. https://www.computerweekly.com/news/366619398/DeepSeek-R1-Budgeting-challenges-for-on-premise-deployments ↩

-

Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜’. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (New York, NY, USA), FAccT ’21, 1 March 2021, 610–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922. ↩

-

Liesenfeld, A., & Dingemanse, M. (2024). Rethinking open source generative AI: Open-washing and the EU AI Act. Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 1774–1787. https://doi.org/10.1145/3630106.3659005. ↩

-

Dell’Acqua, Fabrizio, Edward McFowland III, Ethan Mollick, et al. ‘Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality’. Harvard Business School Working Paper 24-013, September 2023. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/24-013_d9b45b68-9e74-42d6-a1c6-c72fb70c7571.pdf ↩

-

Summerfield, Christopher. These Strange New Minds: How AI Learned to Talk and What It Means. Viking, 2025. ↩

-

“Emotionale KI: Was bedeutet sie für unser Menschsein?” Vortrag vom Philosophen Prof. Markus Gabriel. https://youtu.be/x3xaNApgNWA ↩

-

Vaswani, Ashish, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, et al. ‘Attention Is All You Need’. NeurIPS 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762 ↩

-

LLM Understanding: 23. David CHALMERS. https://youtu.be/yyRzTL201zI ↩

-

Schaeffer, Rylan, Brando Miranda, and Sanmi Koyejo. ‘Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?’ NeurIPS 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.15004 ↩

-

Kaplan, Jared, Sam McCandlish, Tom Henighan, et al. ‘Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models’. arXiv:2001.08361, 2020. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.08361 ↩

-

Lindsey, Jack, Wes Gurnee, Emmanuel Ameisen, et al. “On the Biology of a Large Language Model.” Transformer Circuits Thread, Anthropic, March 2025. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/attribution-graphs/biology.html ↩

-

Andrej Karpathy. Deep Dive into LLMs like ChatGPT: https://youtu.be/7xTGNNLPyMI ↩

-

State of AI in 2026: LLMs, Coding, Scaling Laws, China, Agents, GPUs, AGI | Lex Fridman Podcast #490. https://youtu.be/EV7WhVT270Q ↩

-

Anthropic. “Claude’s Character.” June 2024. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-character — For the full constitution, see https://www.anthropic.com/constitution ↩

-

For a systematic survey of prompting techniques and their sensitivity effects, see Schulhoff et al. 2025. Ceron et al. 2024 demonstrate empirically how small prompt variations shift LLM outputs in the domain of political stance detection. Ceron, Tanise, Neele Falk, Ana Barić, Dmitry Nikolaev, and Sebastian Padó. ‘Beyond Prompt Brittleness: Evaluating the Reliability and Consistency of Political Worldviews in LLMs’. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 12 (November 2024): 1378–400. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00710 ↩

-

François Chollet - Creating Keras 3. https://youtu.be/JDaMpwCiiJU ↩

-

https://arcprize.org/leaderboard ↩

-

AI’s Research Frontier: Memory, World Models, & Planning — With Joelle Pineau. https://youtu.be/nlSK8NA8ClU ↩

-

https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/build-with-claude/context-windows ↩

-

Server-side context compaction for managing long conversations that approach context window limits. https://platform.claude.com/docs/en/build-with-claude/compaction ↩

-

Hong, K., Troynikov, A., and Huber, J. ‘Context Rot: How Increasing Input Tokens Impacts LLM Performance’. Chroma, 2025. https://research.trychroma.com/context-rot ↩

-

Pollin, Christopher. ‘System 1.42: Wie (Frontier-)LLMs “tatsächlich” funktionieren’. Digital Humanities Craft - Research Blogs, 1 July 2025. https://dhcraft.org/excellence/blog/System1-42 ↩

-

Malmqvist, Lars. ‘Sycophancy in Large Language Models: Causes and Mitigations’. Preprint, 22 November 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.15287v1 ↩

-

World Modeling Workshop - Day 1. https://www.youtube.com/live/7Gyuar7nMz0?si=WhdxoTc0Gtia4RB6&t=20566 ↩

-

https://deepmind.google/blog/genie-3-a-new-frontier-for-world-models ↩

-

Snell, Charlie, Jaehoon Lee, Kelvin Xu, and Aviral Kumar. ‘Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters’. arXiv:2408.03314, 2024. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.03314 ↩

-

Chollet, François. ‘Pattern Recognition vs True Intelligence’. YouTube, 2024. https://youtu.be/JTU8Ha4Jyfc. See also: ‘François Chollet on OpenAI o-models and ARC’. https://youtu.be/w9WE1aOPjHc ↩

-

Hochreiter, Sepp. ‘KI Entwicklung, LSTM, OpenAI’. Eduard Heindl Energiegespräch #100. YouTube. https://youtu.be/LG1If4ccEDc. See also: ‘LSTM: The Comeback Story?’. https://youtu.be/8u2pW2zZLCs; ‘Prof. Sepp Hochreiter: A Pioneer in Deep Learning’. https://youtu.be/IwdwCmv_TNY ↩

-

Kambhampati, Subbarao. ‘(How) Do LLMs Reason?’ Talk given at MILA/ChandarLab. YouTube. https://youtu.be/VfCoUl1g2PI. See also: ‘AI for Scientific Discovery’. https://youtu.be/TOIKa_gKycE; ‘Do Reasoning Models Actually Search?’. https://youtu.be/2xFTNXK6AzQ ↩

-

Hubert, Thomas, Rishi Mehta, Laurent Sartran, et al. ‘Olympiad-Level Formal Mathematical Reasoning with Reinforcement Learning’. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09833-y ↩

-

Novikov, Alexander, Ngân Vũ, Marvin Eisenberger, et al. ‘AlphaEvolve: A Coding Agent for Scientific and Algorithmic Discovery’. Google DeepMind, May 2025. https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/DeepMind.com/Blog/alphaevolve-a-gemini-powered-coding-agent-for-designing-advanced-algorithms/AlphaEvolve.pdf ↩

-

Use Case 1 “Patent Cooperation Network”. https://github.com/DigitalHumanitiesCraft/wiiw-patent-analysis-demo ↩

-

Denison, Carson, et al. ‘Natural Emergent Misalignment from Reward Hacking in Production RL’. Anthropic, 2025. https://assets.anthropic.com/m/74342f2c96095771/original/Natural-emergent-misalignment-from-reward-hacking-paper.pdf ↩

-

Wing, Jeannette M. “Computational Thinking.” Communications of the ACM 49.3 (2006), 33–35. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1118178.1118215 ↩

-

Mollick, Ethan. Co-Intelligence. Living and Working with AI. Portfolio/Penguin, 2024. ↩

-

Karpathy, Andrej. “Vibe Coding.” X/Twitter, February 2025. https://x.com/karpathy/status/1886192184808149383 ↩

-

https://github.com/DigitalHumanitiesCraft/wiiw-patent-analysis-demo ↩

-

Pollin, Christopher. ‘Modelling, Operationalising and Exploring Historical Information. Using Historical Financial Sources as an Example’. 2025. http://unipub.uni-graz.at/obvugrhs/12127700. ↩

-

Pollin, Christopher. “Promptotyping: Zwischen Vibe Coding, Vibe Research und Context Engineering.” L.I.S.A. Wissenschaftsportal Gerda Henkel Stiftung, 17 January 2026. https://lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/digitale_geschichte_pollin ↩

-

Use Case 2 “FIGARO-NAM Agentic Workflow. https://github.com/chpollin/wiiw-figaro-nam-demo. Markdown documents are in the “knowledge” folder. ↩